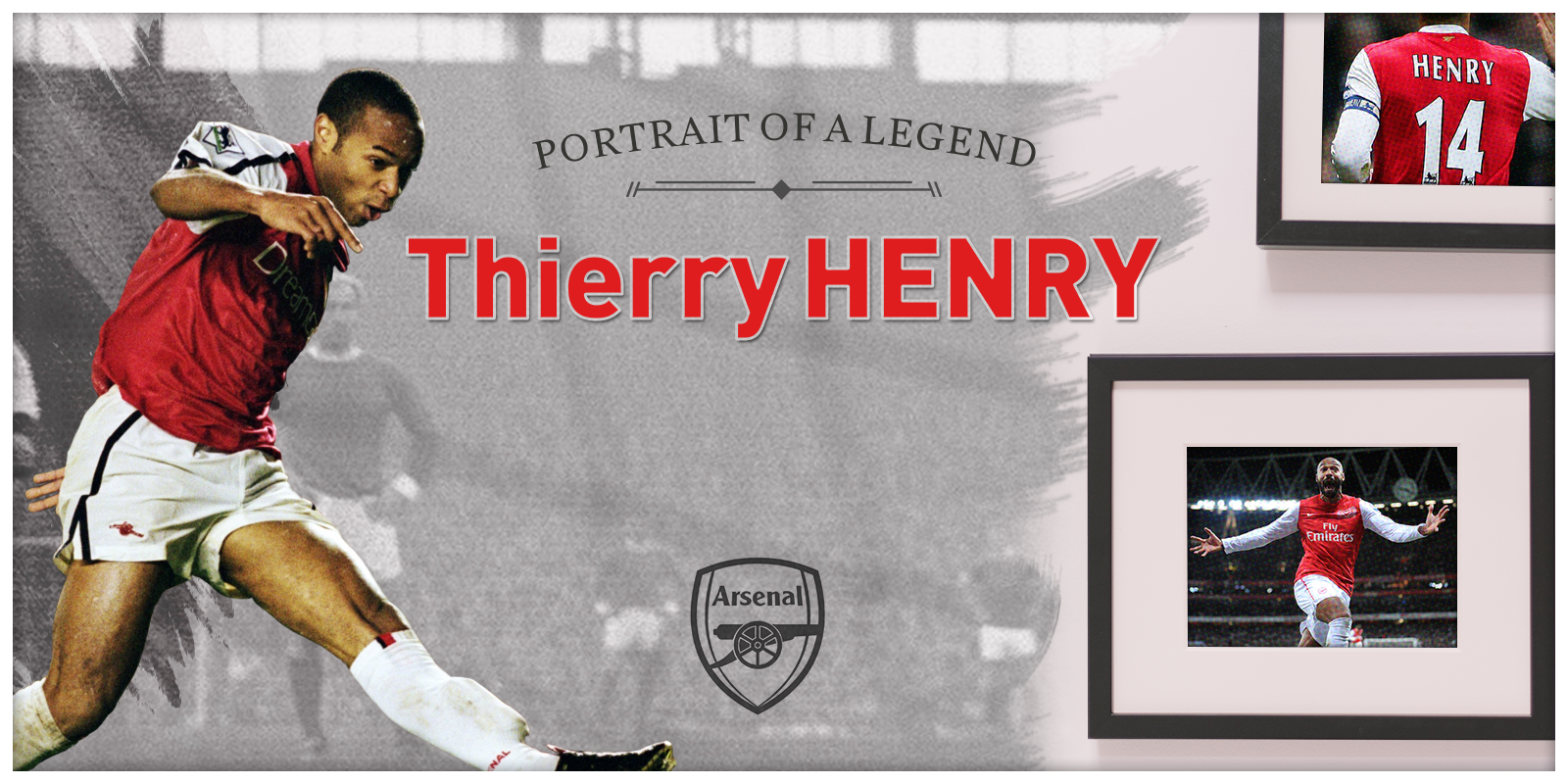

Our hero usually undergoes some dramatic life change during which he shows great courage in the face of adversity, rescues his lady and triumphs over his challenges. To achieve success after one has taken a fall is the ultimate example of human spirit. Thierry Henry boasts no such story. His life has been remarkably linear. He stood out with his gifts in childhood, and he stood out with them when he retired from football.

But if parents play a role in destiny, then Henry became what he was meant to be. Thierry Henry’s story is a story of separation from his father to forge himself, of the people he met along and of finding home.

When he was a child, Henry’s father, Tony, encouraged him to play sports. When his family moved to a small suburbian ghetto of Paris, Henry made the streets his home. He played football there with other kids, often playing on concrete pitches with the only ball in the neighborhood. Everyone wanted to take part. Fifteen or more players formed a team, so a single player would get only a few chances to touch the ball. Henry took this as a sign to keep the ball at his feet for as long as possible and ran with a band of kids chasing after him. He had the speed to do it. Little did he know this would become his trademark as a professional footballer.

Picture: teokon

Picture: teokon

As often as is the case ghetto life presents many dead ends in life. Henry’s father knew it well and stood on the side every time his son played to steer him away from those he considered good-for-nothing. For football-obsessed Tony, his son’s salvation, and his own, lay in football. He had harboured dreams of becoming a professional footballer himself but had only played amateur football as a defender for local side Les Ulis.

‘With him it was never enough, you know, anything I did was never enough.’ Henry said about his father. But while Tony idolized French defender Marius Tresor, Henry had another footballer on his mind: Marco van Basten. Henry was in awe with Flying Dutchman who was scoring at will for Ajax and Netherlands. He tried to emulate every little touch he saw. By the time Henry’s parents had divorced, word of his skill had spread to amateur club Viry-Chatillon. Soon Henry was welcomed there as a 13-year-old. But while Henry’s talents were visible, his new coach curbed his expectations about his future: anything could happen at such tender age and it often did to impede football careers.

He spent two years there before he moved to the prestigious national football training centre Clairefontaine. He slept and trained in their quarters during the week and traveled back home for the weekend. Henry had his first taste of semi-pro football there but the future was still uncertain. His father still went to his son’s games and unleashed furious criticism on coaches and Henry whenever things didn’t go accordingly.

Picture: Mark L

It took a bigger institution to snatch Henry from his father’s tight hold: Arsene Wenger’s Monaco. He didn’t skip three steps at a time on his way up in their ranks. He started for the Under-17 side where he spent two years before Wenger gave him his debut against Nice. Not that Wenger was convinced that Henry would repeat the 30 goals he had scored for the youth team, but he saw him as a gamble in attempt to solve an injury crisis in the first team. Henry, however, characteristically did not disappoint. Wenger later described his first goal as ‘great’–a self-composed curl from the edge of the box.The part he played that first season—three goals in eight appearances—had done enough to turn heads his way.

“He has the capacity to beat defenders; he’s very good with the ball at his feet. He’s a striker for the future.” Gerard Holier spoke about a young Henry in 1994.

When Wenger left for Arsenal and Tigana took over at Monaco, he demoted Henry to the bench with Viktor Ikpeba and Madar flanking star-man Sonny Anderson up front in a 4-3-3 formation. It was two years later, in 1997, when Henry’s tactical acumen, intelligent runs and pace left Tigana with no choice but to start him regularly on the left side of Monaco’s front-line. It was the time when Henry ‘arrived’ in cream fields of football.

But the apex of Monaco and France’s attack had the appetites of another rising star: David Trezageut. The two formed a great striking partnership and friendship right from the onset with Henry occupying the marginal left side. Something was off however. The centrality of Henry’s nature demanded a more central position. It would take Wenger several years later to discover that. As it stood Trezaguet was blocking Henry both at club and national level.

By 1997, Henry had grown from a promising young boy to a man playing for the national side. So when Real Madrid thought they’d found their tasty bite, his father rubbed his hands in delight at the opportunity to orchestrate his son’s move. It was the turning point in Henry’s relationship with his father. His father’s attempts to engineer a move to another club without consideration of Henry’s own wishes left him feeling betrayed. His form took a dip in for a period which later Henry recognized a ‘year in hell’. It was then when he vowed never to leave others to decide for him. In order for him to become a grown man, he must decide for himself. Perhaps this is what spurred him to move to Juventus at 22. It was like showing a middle finger to all that were trying to force him down a certain path.

But there was still one wish that evaded him: playing for Arsenal. Half an hour before he signed his contract with Juve, he had called Wenger, but Les Professor had focused on Nwankwo Kanu instead.

Juventus didn’t sound that bad either. They had triumphed in the Italian league the year before and were the proud owners of a stellar squad including Allessandro Del Piero, Zinedine Zidane, Didier Deschamps, Antonio Conte, Edgar Davids and Filippo Inzaghi. Henry’s intelligence shone through from the beginning. While it may have taken a year or two for his French compatriots who moved there to learn Italian, Henry took several months. His progress on the pitch, however, met more than one hurdle. In Italy, Henry harboured no illusions he would stroll into the first team without a fight. Del Piero had chiseled his position up front in iron while the tactical rigidity of the Italian game imprisoned Henry. He spent eight months in Italy he would rather forget, scoring merely three goals in 19 games.

Picture: Mark L

Picture: Mark L

Then the rescue call arrived: Arsenal had lost Nicolas Anelka to Real Madrid and were ready for him. On August 3, 1999, two weeks before his birthday, Henry transferred home. Wenger had a pleasant surprise for him in the waiting, one that would profoundly change Henry as a footballer. Le Professor moved his new man to a central position.

“It’s sometimes a good idea to deploy a player who has a future in the middle of the park on the flank.” Wenger said later. “A wide player gets used to using the ball in a smaller space, as the touchline effectively divides the space that’s available to him by two; when you move the same player to the middle; he breathes more easily and can exploit space better.” And when you have a player as quick-witted as Henry, it’s a formula for a biblical explosion. The new adjustments on the pitch and Wenger’s package of new diets, short but intense trainings and artistic surroundings contradicted everything 23-year-old Henry had experienced so far.

Henry knew where he stood right from the start with the players too. The squad that had won the double the year before boasted a no-nonsense English core at the back and a genius in Dennis Bergkamp. The vocal Englishmen were quick to introduce Henry to Arsenal by letting him know he would get a verbal whipping if he failed to perform–stern but refreshing approach compared to his experiences in Italy. Another matter was the Highbury crowd. They backed their players with heart: the claps at every pass, every touch and the chants grew on Henry. So did life in London in which he found the polite interpersonal distance of English culture strangely energizing. On the pitch, oppositional players’ hurried to make acquaintances too with their elbows and hard tackles. Understandably, Henry took his first several months adapting to this avalanche of changes.

By November, he had started speaking English fluidly. By December, he had started bagging goals. By May, he had scored 16 goals, one less than Anelka the season before, and had cemented his place as Wenger’s number one striker. Henry had discovered his real va-va-voom.

His reputation preceded him on grounds around England too. People saw his refusal to take dives as an endearing quality. Henry was sailing in smooth seas. Results shadowed closely behind. Henry played in 189 matches for Arsenal from 2001 to 2004. He bagged 120 goals along the way.

Picture: Mark L

Picture: Mark L

At the peak of his Arsenal career he terrified oppositional defenders with his mere presence. His teammates aimed the ball at him even if he was in his own penalty box. He often left flocks of defenders behind him, sometimes looking like ridiculously scattered bowling pins. His father must have felt devoid of words in moments like these: his son had outdone even his sky-high expectations. The same expectations that burdened Henry’s younger version, he now carried with ease as Arsenal strolled to two more domestic titles, one of which was the historic 49-undefeated run. It was symbolic of how far he has gone on his journey of becoming his own man.

Henry had one man to thank for all that: Wenger. In Le Professor, he had found his second father, his mentor. Fast-forward ten years later, the depth of their relationship was most clearly showed in that embrace at Henry’s goal against Leeds on his loan return spell in 2012: Henry running with arms spread carried by the euphoria of a packed Emirates stadium, yelling his lungs out, embracing Wenger as if to say ‘Thank you for this. I will never forget what you gave me.’ Beating the sewn crest on his chest as if to say ‘Yes, that’s me, that’s me, I am Arsenal.’

When he moved to Barcelona in 2005, the front of a footballer with career progress in mind always verged to crack. Henry’s mouth spoke the numbers but his face told the truth: he had left his heart in London. But what he had build in England, he took with him. He carried this presence in the dressing rooms of Barcelona where even the best footballer of his generation Lionel Messi admitted, undoubtedly star-struck, he could not even ‘look Henry in the eyes’ at first. And while all was good on the surface, there was an air of exile about him.

Trouble followed on the international front. First it was the fiasco of France’s South Africa World Cup and then his handball against Ireland. Henry felt attacked and shamed, his image took a hit. He suffered.

In 2010, he sailed to the new world of America to play for New York Red Bulls. By then he had won everything on club and international level. He had cemented his place as one of football’s legends. He had left a legacy: the best striker that had never won the Ballon D’or.

‘Ballon D’or? A bunch of journalists and people voting for their friends.’ the ever-outspoken Johan Cruyff once said. He might have been pissed off at Henry reaching second for the prize in two successive years.

But accolades could never encompass the full story with Henry. It was about the people he met along the way in his illustrious career and the impression he left them with, about destiny and his battle with it to define himself as a man and footballer; about finding home. “You must be the man you carry inside.” Henry told a journalist in 2008. This hard-learned lesson carried him to the heights of football, but, more importantly, helped him discover that the man he carried wore a canon on his chest and loved the grass of Highbury and Emirates. This was the man Henry missed and wished to return to.

Some say Henry is stuck in a memory, but in truth, home is an elusive place that requires hard work to keep. Henry learned that the hard way. He never quit on working to get it back either.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8pSR-E9vZo

Check out Thierry Henry’s autobiography: Lonely at the Top on Amazon

Author

The Football Coach

How To Win Football Bets: A Betting Strategy To Help You Win Every Time

The Football Coach

How long is a football pitch? The complete pitch size guide